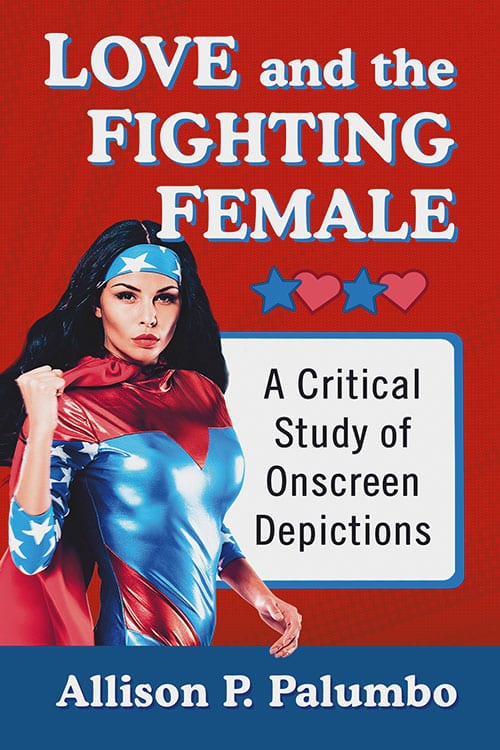

Love and the Fighting Female

A Critical Study of Onscreen Depictions

$39.95 Original price was: $39.95.$31.99Current price is: $31.99.

In stock

About the Book

The fighting female archetype—a self-reliant woman of great physical prowess—has become increasingly common in action films and on television. However, the progressive female identities of these narratives cannot always resist the persistent and problematic framing of male-female relationships as a battle of the sexes or other source of antagonism.

Combining cultural analysis with close readings of key popular American film and television texts since the 1980s, this study argues that certain fighting female themes question regressive conventions in male-female relationships. Those themes reveal potentially progressive ideologies regarding female agency in mass culture that reassure audiences of the desirability of empowered women while also imagining egalitarian intimacies that further empower women. Overall, the fighting female narratives addressed here afford contradictory viewing pleasures that reveal both new expectations for and remaining anxieties about the “strong, independent woman” ideal that emerged in American popular culture post-feminism.

About the Author(s)

Allison P. Palumbo lives in Moses Lake, Washington and teaches English and gender studies courses at Big Bend Community College. They have written previously about Henry Miller’s Tropics trilogy as well as Dorothy West’s The Living Is Easy, and their research and teaching address sexual politics and gender issues in 20th-century American literature and popular culture.

Bibliographic Details

Allison P. Palumbo

Format: softcover (6 x 9)

Pages: 245

Bibliographic Info: notes, bibliography, index

Copyright Date: 2020

pISBN: 978-1-4766-7739-2

eISBN: 978-1-4766-3977-2

Imprint: McFarland

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments vi

Introduction 1

One. To Love, Honor and Be Oppressed: The Problem Hetero-Romance Poses for Feminism 21

Two. Mixing Business with Pleasure: Love-Buddy Fighting Females and the Politics of Romance in the Workplace 32

Three. The Struggling Romaction Genre: Love-Warrior Fighting Females and the Politics of Romance on the Homefront 81

Four. What Doesn’t Kill Her Makes Her Stronger: The Fighting Female as a Survivor 123

Five. Women Leaders and the Men Who Love Them 175

Conclusion 202

Epilogue: Evolving Pleasures 216

Chapter Notes 219

Bibliography 225

Index 233

Book Reviews & Awards

“Detailed textual and cultural analyses that will be useful to anyone interested in cultural, media, and gender studies. The language is accessible throughout…recommended”—Choice

Author Interview

This interview appeared on SciFi Pulse February 14, 2020.

Nicholas Yanes talks to Allison Palumbo on their academic career and Love and the Fighting Female.

Nicholas Yanes: Growing up, what pop culture franchises were you a fan of? Are there any that still make you feel young?

Dr. Allison Palumbo: The closest I can think of in terms of franchises from my youth: superheroes—the Bionic heroes, the DC heroes onscreen (Superman and Wonder Woman), cartoon heroes, and even The Greatest American Hero. But I also loved adventure franchises like Star Wars, Star Trek, the Romancing the Stone movies, Indiana Jones, and Alain Quartermain. In fact, I just returned from watching The Rise of Skywalker, and I’m tingling. There’s still something of a rush for me when I watch people who bravely face challenges and obstacles that scare them because they are motivated to protect something important, even in the case of people who have powers that should give them the confidence they needed, and that was the rush I felt when I was younger.

Yanes: As a fellow academic, I am aware that many scholars are researching popular culture. Why do you think this field has grown so quickly?

Palumbo: A few reasons: Writing about popular culture has begun to break free from the long-standing tendency to argue back and forth about whether or not “low” culture is a worthy site of deep analysis, and mass media began to be accepted as a legitimate subject of rigorous study. It’s also a lot of fun, being dedicated to critically exploring the implications of, movements surrounding, and complications within pop culture texts.

Additionally, there has been a proliferation of mass media and multiple forms of popular culture since the end of the 20th century that provided more engaging and personal connections for scholars to explore their obsessions. Related to that is that various standpoint theories and expressions of identity politics emerging from the 60s, 70s, and 80s that provided new perspectives from which to critique popular culture.

Having said that, I don’t see the interest in popular culture as having grown that much in some ways, considering that theorists have been writing about popular culture regularly throughout the 20th century—Barthes and Derrida, Benjamin and Baudrillard, Jameson and Hassan and McCluhan, Greer and Friedan and Douglas and Kael and Bordo and Mulvey. We just have more to explore and more people who want to do it, thanks to the extensive work and the proof of value foundational scholars provided—whether one likes the texts emerging from mass culture, they definitely help us understand more about how culture influences people’s understanding of what it means to be human in the world today.

Yanes: From a professional standpoint, do you worry that this field is becoming too saturated with scholars? For instance, if a student said they wanted to pursue a career in academia studying popular culture, would you think that is a good idea?

Palumbo: Possibly, it’s getting too saturated. Tenure-track jobs in academia seem to become more scarce every year due to the adjunctification of the field (which seems to have a larger influence than the reduction of program sizes, though that is also the case). I would encourage students as much to continue pop culture research as to continue work in literature (my other area), but I would do it by being open and realistic about the obstacles and possibilities. Someone has to get those jobs, and why not try if it’s what a student loves? That was my own perspective when I began pursuing my English studies. I would never want to encourage someone to give that up purely because of the practical realities. But that’s because I am confident in the value of those studies in the first place. If a student focuses on popular culture in their studies, that doesn’t mean they won’t gain other important skills they could apply to the alt-academic careers out there should a career in academia not be available.

Yanes: Your recent book is Love and the Fighting Female: A Critical Study of Onscreen Depictions. What was the inspiration behind this book?

Palumbo: Two great classes at the University of Kentucky that I took shortly after I began my Ph.D. studies, where I went to work with Susan Bordo. The first was a class on women heroes that provided my first opportunity to analyze a film for the final essay (I chose Coline Serrau’s Chaos.). Doing that work entranced me and allowed me to explore and express so much of what until then I had not considered useful critical thinking work. I mean, I had always loved watching movies as much as reading, but I had never thought of it as “worthy” of scholarly attention or really attempted to make sense of it beyond surface effects.

Then, for class on intimacy and cinema taught by Virginia Blum, I wrote a paper on Mr. and Mrs. Smith (2005) and the Romaction genre. She nominated my essay for an award in the department, and it won. That essay became the basis of my dissertation (and it’s now part of Chapter Three). Virginia’s championing of my work made me feel more validated and capable in my abilities to form ideas about film as a text. When I brought the possibility of changing my entire focus to Susan, she was totally on board, and she was an excellent advisor and guide throughout the process.

One important related aspect that solidified my determination to turn the work into a book was that whenever I would tell people about the work I was doing, they would respond with enthusiasm, and it often inspired them to begin thinking more critically just in their attempts to discuss it with me and to offer other recommendations of what I should watch and why. As a long-time teacher dedicated to helping people get more excited about analysis of any kind, the enthusiasm of strangers inspired me to want to write more about what they engage with every day, usually without thinking about it, in the hopes that I could engage them more. I’ve seen this work in the classroom now in ways that further galvanize my research goals. So, I found my audience, so to speak. I want my work to be as well-researched and argued as possible so that I create something meaningful and challenging that contributes to my academic field, but I also want it to speak to a variety of readers.

Yanes: While doing research for Love and the Fighting Female, did you gain any insights that took you by surprise?

Palumbo: Well, the sad surprise that emerged as I finished the outlining of the project was really just how heteronormative, white-washed, and objectified women onscreen continue to be today, even those who supposedly reflect new conceptions of modern womanhood that break just about every other female/feminine stereotype. However, I plan to explore those arenas more specifically in my second book.

In terms of the research I was doing, I was pleasantly surprised how some shows held up, even though I was watching them again twenty or more years later (Remington Steele and Moonlighting, in particular—the finale of Maddie and David’s volatile relationship still makes me cry. I’m so sad they couldn’t make it as partners and friends.). Other programs did not hold up as well (Bionic Woman and Scarecrow and Mrs. King). I was also surprised how I felt more positive, overall, about women’s roles in the media afterward; even with all of the lingering problems, there really have been changes, and they have impacted people, and they are continuing. That gives me hope, which helps counterbalance the frustration I still often feel.

One of the biggest surprises for me was how much more I understood the impact that seeing female bodies perpetrating violence has on me, why I have sought these narratives out so much in my own viewing history. At the end of the project, I was thoroughly convinced by Jack Halberstam’s assertion about the way “imagined violence” can change perceptions of subordinated groups in a culture through repeated mass media images of them fighting back, embracing aggression. People thus learn to see victims of oppression also as people who are fed up, who won’t take it anymore, and who have the means, drive, and/or skills to follow through on that. I don’t see violence as an answer to just about anything—I am very invested in people using healthy and thorough communication to improve humanity and human experiences for everyone. However, I do see and champion the value in some fantasies of such violence.

Yanes: For this project you examined films and television shows from the 1980s to present. While I love Xena and Buffy, are there any shows featuring fighting females that you think are overlooked?

Palumbo: Both are classic texts—and Alien. Those are probably the three most commonly referred to fighting female pop culture texts I encountered, and while they are excellent and worthy of research, it seemed they popped up everywhere. I used that to help me make decisions about the kind of texts I would discuss, to try and mix up the options. However, my main motivator was to look at more “realistic” versions of women’s who kick ass (as realistic as any fictional character can be)—the ones who didn’t have powers or weren’t alive in a fantasy world or future, the ones who can be easily overlooked for action cred, which makes them all the more awesome from my perspective. I mean as a viewer, I certainly love the heroism, and I did look for characteristics of those over-empowered-and-able heroes in myself, but their options for fighting back and the circumstances dictating their struggles are so far from possibility and so disconnected from the world I live in that it almost seems to dampen the empowering aspects of their actions.

For example, the way I define fighting female is that she has to use her body or a weapon, successfully, in some violent way, to save herself or others. That’s key to her gender transgressions and role as a hero. Well, in Prime Suspect, Helen Mirren’s character doesn’t pick up a gun until near the end of the entire series, but it’s super powerful when she does, and it kind of defines her character in an important way, that ability to use violence when necessary, that the rest of the narrative couldn’t quite capture.

For good reasons, the tendency for some feminist media critics has been to look at women who portray the lone wolf or who are partnered with another woman, and I saw that as a potential opening to explore. For example, I really like women who are key players in male-oriented or partnered texts, like Yvonne Strahovski’s character Sarah Walker in Chuck or Stana Katic’s character Kate Beckett in Castle. Still, I do include characters who fit the lone wolf as well, like Lisbeth Salander, who is one of my favorites right now. She embodies so perfectly the “survivor” identity, navigating her victimhood and her agency in ways that really speak to me—and I imagine to others like myself who have had to deal with that in their own lives—only she got to go the next mile and take down those motherfuckers, too, and do it in ways that would help others [I’m not sure if profanity is ok, but I am going with it]. Elizabeth Moss’s Detective Robin Griffin in Top of the Lake is another one I discuss, as is Jessica Jones (Krysten Ritter). I like their dark and gritty humanity, watching the struggles they face, struggles we don’t see in male-bodied action heroes, even those who are rendered vulnerable at some point in the narrative (as most heroes must be). I talk more about this in Chapter Four.

I also address some unexpected bad ass women, like the hyper-intellectual Temperance Brennan (Emily Deschanel) in Bones or Claire Foster (Tina Fey) in Date Night. They portray different forms of aggression and ability that most people would not immediately think of as strength and that defy gender expectations, and I always enjoy that. Then there are the awesome women of Black Lightning: Nefessa Williams, China Anne McClain, and Christine Adams, who I am sure will get more scholarly attention once the show gets more play. I love the storylines and the ways their characters grapple with more of the daily drama of being a protector. They are some of only a few superhero women I address in the book.

And I don’t know if it’s being overlooked right now—I haven’t read responses to it yet, but Killing Eve is incredibly important AND incredibly good. It’s so compelling!

Yanes: We live in an era in which there are more superpowered women than ever before. However, they all tend to have similar body types. Regardless of race and age, they mainly tend to have petite bodies. (In contrast, the world of prowrestling has a wide variety of female body types.) Why do you think the bodies of fighting females are often limited to one type of figure?

Palumbo: This is a terrible problem—pervasive, destructive. I think when it comes down to it, the slight body is the less intimidating body. I mean, even throwing some serious tone on woman (a la Linda Hamilton in Terminator 2), it’s still on a slight body, one that is generally significantly more slight than most men in action. In terms of strong women onscreen, gaining access to not just the representation of power in the text but also the representation of autonomy through power (something that many fighting female characters don’t always embody) is still something of a novelty, and as I tell my students, making her visually appealing in a stereotypical feminine way is the pop culture sugar that helps the medicine of a transgressive female body go down.

The overrepresentation of men in production and the continued primary valuation of women as objects are both contributors as well, as are misapprehensions about audience interest related to both. For example, the money people in the media assume young men are the reason that movies make money (and up until more recently, this has tended to be the case) and that women-driven films won’t bring the men, so producers want to hedge their bets against that and find a way to entice those men. But that’s such a limited (and limiting) conception of male audiences that assume 1) all these men are heterosexual, 2) men need to be manipulated by eye-candy because they are dumb lugs motivated only by their sexual impulses, and 3) that men’s preferences for certain bodies in the first place aren’t as much media influence as biology.

Money-makers’ conceptions totally ignore audiences like myself who are non-binary and somehow impossible to conceive of in terms of appeal, and they still tend to be derisive of appealing to female audiences (who are assumed to go to what their boyfriends go to—again, the heteronorm—and who supposedly don’t like action as much—both proven wrong by recent numbers). All this even with increasing proof that not only can movies headlined by women make money, but that movies about women’s lives and that feature different types of female embodiment are appealing.

The only bodies that challenge the status quo, like those you mention in wrestling, or those of Olympic athletes and tournament winners, tend to be in niche arenas of interest. That being said, there is a growing interest among viewers like myself for more diverse bodies. I can’t wait for the first blockbuster action film that features a thick, muscled female-bodied actor as the lead in a full-on action drama (but not super-pumped because I don’t even agree with those on male forms). I mean a widespread appealing movie and bodies that exude physical strength. We get glimpses now and again: Xena and her powerful body, Michelle Rodriguez’s boxer form in Girlfight, Melissa McCarthy’s awesome agent character in Spy, or Brianna Hildebrand and Gina Carano in Deadpool (Carano has featured in leading roles but again in films that have a smaller audience.). There, that’s five I can think of right offhand. Not much progress. Anyway, that’s where the changes tend to come, from the smaller productions, which seem to act as a kind of beta testing area for female types before they proliferate. (As many fans know, some of the first most violent kick ass women onscreen were in varied exploitation genres, like the women in prison films, Russ Meyer’s violent fantasy starring Tura Satana, and the “badass bitches” of blaxploitation like Coffy, Foxy Brown, and Cleopatra Jones).

Yanes: While no show or movie is perfect, what current media properties to you think best represent fighting female characters and their relationships to others?

Palumbo: The aforementioned Black Lightning, Killing Eve, Castle, and Mr. and Mrs. Smith are some of my top contenders. So is Captain Marvel, and I was pleased with the developments in Marvel around The Avengers in general with the last installment. I also like Elementary and Person of Interest for their portrayal of varied kinds of male/female relationship dynamics. I also thought that Rizzoli and Isles, Spy, and The Spy Who Dumped Me really represented positive relationships between women—women who gas each other up, so to speak, in ways that Buffy and Xena did.

Yanes: When people finish reading Love and the Fighting Female, what do you hope that they take away from it?

Palumbo: First, an understanding of the power of stories—every kind of story—and just how much they teach us about being human in the world. That’s at the base of my desire to help people better navigate those stories, to understand their implications and motivations and cumulative effects.

Second, that female-bodied people can identify as strong and independent and not have to sacrifice love—though they may have to sacrifice narrow conceptions of love and romance that are counterproductive, that would undermine their strength and independence. Much of romance today is a product of modified patriarchal systems that maintain a basis of female subordination to male-bodied/masculine-related inventions of strength and independence—these repress the Other, difference, multiplicity, and the complexities of human identity. This is ingrained in institutions like the economy, politics, and the family, which I show throughout the book.

The only reason that the very traits of strength and independence have been seen as the opposite of dependence (rather than required for functional and healthy interdependence) is because the relationships and emotional and relational labor that sustain those traits have been rendered invisible (because they are conceived of as female or feminine work), which allowed some men the ability to experience the world seemingly unfettered, but that’s just not true. The answer is not for women and men to continue to divide strength and independence from the work that sustains it but to undermine and refashion our entire understanding of what it means to be strong and independent.

Finally, we need to make our stories about love better. People need to see the relationship changes they want to live, and there is so little onscreen that doesn’t replay sexist, androcentric, homophobic, female-subordinating and/or male-limiting themes, particularly in portrayals of heterosexual relationships. The way we think about love in gendered terms is in part responsible for problems in human relations in general. Love is something that is used to hold us all back. Love should liberate us to be the best of ourselves; it can be a state of connection that feeds our best ambitions. It will always come with conflicts—that’s what happens when people interact, it’s inevitable. Yet, those conflicts can be generative if both parties have been raised to identify as a subject and embrace their autonomy in relation to others’ autonomy—if that autonomy is given expression and representation through the cultural imagination as being a norm for all people and not for only the right kinds of people. That is what will allow people to better approach love from a partnership orientation (to use Riane Eisler’s phrase) that will encourage more truly equitable and egalitarian interpersonal relationships.

Yanes: Finally, what else are you working on that people can look forward to?

Palumbo: I’ve mentioned my current obsession with Black Lightning, which I’ve been thinking about in terms of the politics of respectability and intra-racial relationship conflicts and the way those emerge from interconnected forms of gender subordination, racism, and classism. In my spare moments, I am trying to see where that will go. But I see it as the beginning of the second half of my fighting female project, where the next book will focus on the relationships between women, both romantic and platonic, strictly platonic male/female relationships, and depictions of race in relationships. Texts that offer such relationships in the mass media have only recently become more widespread, and I am excited about what that means for the future of fighting females onscreen. I have also toyed with a kind of encyclopedia of unhealthy love representations in which I characterize and categorize all the unfortunate messages romance-based narratives send: from ‘quit your job and give all your money to a strange, mean white man down on his luck!’ (French Kiss) to ‘stop-being a bitch and be nice, so I can love you already’ (too many movies to count). I want to see the bitch do her thing, and if she wants, still get the love, and I think I’m not alone in that.