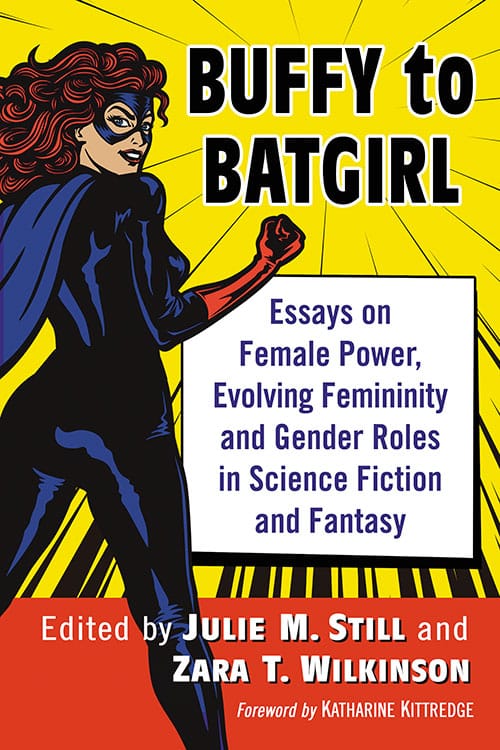

About the Book

Science fiction and fantasy are often thought of as stereotypically male genres, yet both have a long and celebrated history of female creators, characters, and fans. In particular, the science fiction and fantasy heroine is a recognized figure made popular in media such as Alien, The Terminator, and Buffy, The Vampire Slayer. Though imperfect, she is strong and definitely does not need to be saved by a man. This figure has had an undeniable influence on The Hunger Games, Divergent, Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and many other, more recent female-led book and movie franchises.

Despite their popularity, these fictional women have received inconsistent scholarly interest. This collection of new essays is intended to help fill a gap in the serious discussion of women and gender in science fiction and fantasy. The contributors are scholars, teachers, practicing writers, and other professionals in fields related to the genre. Critically examining the depiction of women and gender in science fiction and fantasy on both page and screen, they focus on characters who are as varied as they are interesting, and who range from vampire slayers to time travelers, witches, and spacefarers.

About the Author(s)

Julie M. Still is on the faculty of the Paul Robeson Library at Rutgers University. She has published and presented on several topics relating to librarianship, history, and literature.

Zara T. Wilkinson is a reference librarian at Rutgers University-Camden. In addition to her research interests in librarianship, she has published and presented on the depiction of women in science fiction television shows including Star Trek, Doctor Who, and Orphan Black.

Bibliographic Details

Edited by Julie M. Still and Zara T. Wilkinson

Foreword by Katharine Kittredge

Format: softcover (6 x 9)

Pages: 252

Bibliographic Info: bibliographies, index

Copyright Date: 2019

pISBN: 978-1-4766-6446-0

eISBN: 978-1-4766-3725-9

Imprint: McFarland

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments v

Foreword by Katharine Kittredge 1

Introduction (Julie M. Still and Zara T. Wilkinson) 5

I. Images of Female Power

Something Wicked This Way Comes? Power, Anger and Negotiating the Witch in American Horror Story, Grimm and Once Upon a Time (Alissa Burger and Stephanie Mix) 9

Witches, Mothers and Gentlemen: Re-Inventing Fairy Tales in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Kerry Boyles) 33

Selfish Girls: The Relationship Between Selfishness and Strength in the Divergent and Tiffany Aching Series (Alice Nuttall) 53

“Have good sex”: Empowerment Through Sexuality as Represented by the Character of Inara Serra in Joss Whedon’s Firefly (Patricia Isabella Schumacher) 61

Girl Power and Depression in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (Shyla Saltzman) 85

II. Evolving Femininity

Girl Rebooted: Transforming Doctor Who’s Sarah Jane Smith from Sidekick to Hero (Sheila Sandapen) 101

The Evolution of Lois Lane: Reflections on Women in Society (Sandra Eckard) 116

Alternate, Not Arrested Development: Bryan Fuller’s Female Protagonists (Trinidad Linares) 129

III. Re-Framing and Re-Forming Gender Roles

Vampires Who Go to High School: Everyday Women’s Culture in Twilight, Dracula and Fifty Shades of Grey (Caolan Madden) 157

Using the Animator’s Tools to Dismantle the Master’s House? Gender, Race, Sexuality and Disability in Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time and Steven Universe (Al Valentín) 175

“Little Geisha Dolls”: Postfeminism in Joss Whedon’s Firefly (Peregrine Macdonald) 216

Beyond the Monomyth: Yuriko’s Multi-Mythic Journey in Miyabe Miyuki’s The Book of Heroes (Eleanor J. Hogan) 225

About the Contributors 241

Index 243

Author Interview

Rutger’s Today interviewed Julie M. Still and Zara T. Wilkinson on September 24, 2019.

Rutgers–Camden librarians Julie Still and Zara Wilkinson examine the roles of the heroine and gender in a new book of essays.

Science fiction and fantasy have burst into the mainstream in recent years, with blockbusters from the Marvel Cinematic Universe setting box office records and series like Harry Potter spawning multimedia franchises worth billions of dollars. Despite this seemingly universal popularity, we often associate these genres only with male characters, creators, and fans.

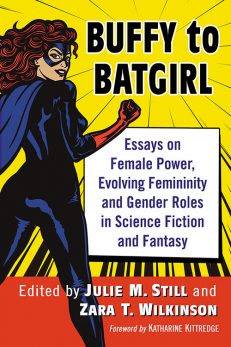

Buffy to Batgirl: Essays on Female Power, Evolving Femininity and Gender Roles in Science Fiction and Fantasy, published this month by McFarland and edited by Rutgers–Camden librarians Julie Still and Zara Wilkinson, aims to deepen our understanding by examining the role of the heroine and of gender in science fiction and fantasy.

In recognition of National Comic Book Day, we spoke to Still and Wilkinson about what we stand to gain by broadening the discussion about women and gender in these increasingly popular genres.

We tend to think about fantasy and science fiction as male-dominated genres, with women characters often playing the role of damsels in distress. But your book demonstrates that this is not always the case. How do these genres represent women in positions of power?

Wilkinson: Women have written science fiction and fantasy for as long as the genres have existed, but science fiction especially has long been viewed as a male domain. However, the publication of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is generally viewed as the birth of science fiction, meaning, of course, that this male-dominated genre was invented by a young woman. Even in visual media, early representations of women weren’t without nuance. Dorothy and the witches in the book The Wizard of Oz (1900) are all pivotal and powerful characters, and they continued to be so on film. Early film serials introduced characters like Dale Arden (Flash Gordon), Wilma Deering (Buck Rogers), and Lois Lane (Superman) who, despite being love interests for the male protagonists and occasionally in distress, were also smart and career-oriented. While Lost in Space saw the Robinson women tending to duties such as laundry and food preparation, Star Trek quickly followed, including women in positions of authority—even if in traditionally female occupations, such as nursing and communications.

Still: In the mid-1970s female characters started appearing more regularly and became more powerful. Wonder Woman and the Bionic Woman took over the television. In literature, around the same time, a number of genre books introduced female lead characters, including those created by Anne McCaffrey and Patricia McKillip. Ripley’s starring role in Alien is often considered to be a watershed moment, and she was of course followed by Sarah Connor in Terminator, Buffy in Buffy, the Vampire Slayer, and many others throughout the decades since. Girls today have many more role models in science fiction and fantasy, although certainly there is still room for improvement.

How has the depiction of the female hero changed over time, and what can we learn from this evolution?

Still: The existence of the “female hero” is itself a change. Women can be the star of their story, rather than a supporting character in someone else’s narrative. This naturally means that women are less often cast as merely damsels in distress and, as characters, have more agency—more control over their own lives and futures. Women can be starship captains, superheroes, vampire slayers, tributes representing their district in Hunger Games, and just regular people thrust into interstellar or interspecies battles. Women don’t have to be love interests with a penchant for getting captured, they also don’t have to be tough action heroes or characters without flaws. Men have long been depicted in media as multi-dimensional people who have strengths and weaknesses, jobs, families, interests, and personalities. The same should be true of women. Science fiction author Joanna Russ famously said, “There are plenty of images of women in science fiction. There are hardly any women.”

How have science fiction and fantasy reframed the role of women in society?

Wilkinson: Science fiction and fantasy have a long history of social commentary. A good example of this is “Let That Be Your Last Battlefield,” a Star Trek episode in which the crew of the Enterprise discovers two warring groups who both have skin that is half black and half white—but on opposite sides. That is the reason why they are at war, and the crew cannot understand why a mere cosmetic difference would cause so much trouble. It is easier to critically examine something when it is displaced onto another culture or setting, because the distance gives you a new perspective. It can be easier to imagine something new or innovative when it is removed from reality. Science fiction and fantasy provide opportunities for that, too. We can imagine women captains and women in space there before we see them in real life. More generally, we can see women in positions of authority, enacting change and making a difference in the world around them.

Still: If you just take one example, the character of Lt. Uhura on the original Star Trek television series. When she was thinking of leaving the series Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., asked her not to, as she was an important symbol. Whoopi Goldberg remembers seeing Uhura on television and the impact it had on her. That’s just one character on one show. Representation matters. On a personal level, some of my earliest reading materials was my brother’s X-Men comic books. The first television show I remember seeing was an episode of the original Star Trek series. These made a real impression on me. I saw Jean Grey and Lt. Uhura and read sci fi and fantasy books about other girls and women doing all these exciting things and it inspired me to aim higher myself.

In what ways are comic books an important medium for women readers?

Wilkinson: Although comics are often associated with men, recent estimates suggest that women are responsible for about 40 percent of comic book sales. The comics and graphic novel landscape is increasingly populated by prominent female creators, from Gail Simone, G. Willow Wilson, Kelly Sue DeConnick and Noelle Stevenson to Marjane Satrapi and Alison Bechdel. Despite this, many of the most popular comic book franchises are about male characters, and there is a pervasive common wisdom that comics about female characters don’t sell and comics-inspired films about female characters don’t do well at the box office. Women and girls need to be able to see themselves in The X-Men and The Avengers, but also in comic book shops and at comic conventions. The same is true of people of color, people with disabilities, the LGBTQA community, and any group who has struggled to find themselves reflected in mainstream popular culture.